Joseph Arnold Sadler

Date of birth: 9.2.1894

Date of death: 4.11.1969

Area: Normanton

Regiment: King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

Family information: Son of Mary Ann Sadler, 24 Beck Street, Normanton

Rank: Sergeant

Service number: 2945/200784

War Service

My father, Joseph Arnold Sadler was born on 9th February 1894 to Mary Ann Cowburn and Joseph Sadler. He had three elder siblings, Bertha, Arthur and Miriam and two younger ones, Walter Graham and William Ewart. His father died at the age of 48 in 1906 when my father was 12. Arnold worked first as a telegram boy at Normanton Post Office and then he worked in the mines.

The mineowners offered the men 30/- if they would join up and I think he probably took this and joined up practically at the outbreak of the war because he was in France by 13th April, 1915 and there would have been a period of training. He was 20 years old at the time.

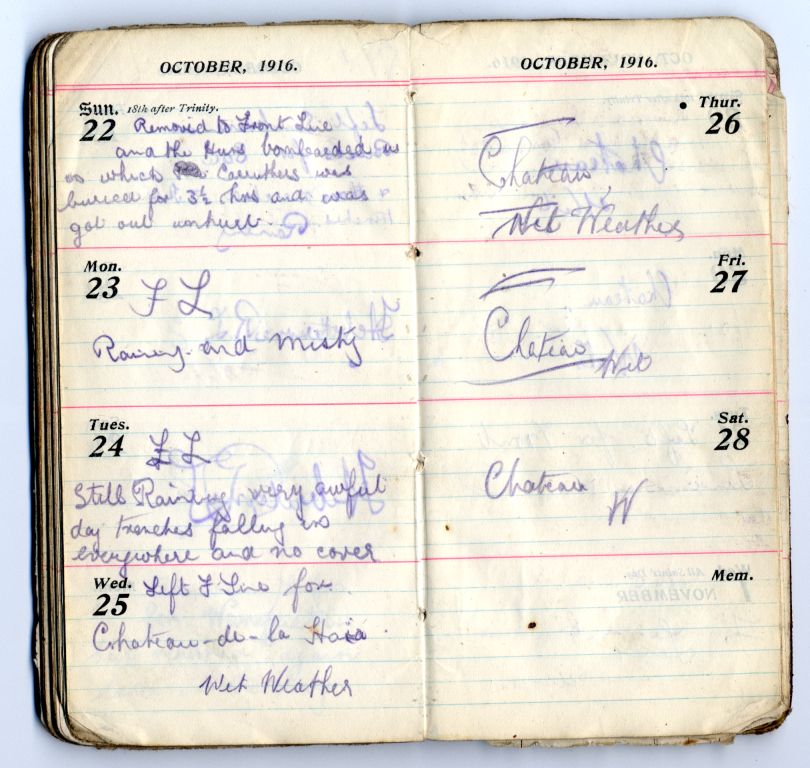

His regiment was the 1/4th K.O.Y.L.I., his company ‘D’ Company and his rank and number were Sgt. J.A.Sadler, 2945. He made a note, in the diary that he kept for 1916 of his promotion through the ranks, becoming a Corporal on the 19th September 1915, a T/Sgt (which I take to be a temporary sergeant) on the 22nd November 1915 and a Sgt. on the 1st May 1916.

One of his jobs in the army during 1916 was the purchase of provisions and after having collected 10/- from each sergeant, the Company Sergeant Major and the Company Quartermaster Sergeant, he bought food from the Canteen which included best chocolate, 6/-, salmon and fruit, 9/-, peas and potatoes, 4/- and eggs 5/2 ½ d. and the canteen at Hedanville had to be paid 8/5d.

During 1916, the 1/4th K.O.Y.L.I. moved around quite a lot, sometimes spending a few hours in a place and at other times spending many days in other places. On the 9th February 1916, he makes quite a poignant remark in his diary. “My birthday and the second spent away from home. Hope it is the last”. In the same month he went into the reserve trenches at Authuille. There was plenty of snow and the trenches were very cold too. After a few days, when the snow began to thaw, there was plenty of water in the trenches also.

March of that year was a mixture of extremes, one day it was very bad weather – snowing, and the next day it was very hot weather. He started working on the railway sidings at Arquevres and finished 10 days later. He also did a route march, a church parade and he went on a gas course to Varennes for seven days. After Arquevres, came Rubiempré, Talmas, Candas, Avuley Wood, Harponville, Senlis, Contay and back to Avuley Wood for the 1st July, the Big Push, the start of the Battle of the Somme. Throughout the battle he was moved between the reserve trench, the 2nd line and the front line. He encountered heavy fighting during September with several killed and wounded and also there was a smoke attack and one little memo in his diary reads:

“ later the previous night and early morn the enemy heavily shelled us but we had no casualties”. He continued to be moved about between the reserve trenches, the second line and the front line throughout October and November and was then admitted into hospital at Gaudiempré and then on to a rest camp. The whole of December was spent at Humbercourt.

I don’t know exactly when, probably in 1917, but my father was in a mustard gas attack and was hospitalised and given just six weeks to live. His mother was sent for but she was too ill at the time and his sister, Miriam, went to France to see him. As a result of this gassing he lost one lung. When he was discharged from the army he was given the choice of taking a pension or taking a lump sum, so he took the lump sum as his prognosis was now 12 months to live. He was awarded the Victory, British and 1914/15 Star medals.

Family Life

He rarely talked about the war and used to say it was all in the past although on some occasions he would answer specific questions. He used to tell me about catching mice as they ran up his trouser legs when they were in the trenches and about his friend getting blown up at the side of him. I also once asked him directly if he had killed anyone and his answer was “probably”. He also told my sister that they had to share a pot of water to shave in and if you were the last to shave it was all hair and no water. He also told her that they had to run up the seams of the trousers with a candle of a lighter to get rid of the bugs. One other thing he said to her was that when he was in the army they used to ask “who would like to go on a bombing course and if you volunteered, they strapped two bombs on you and sent you over the top”. Unfortunately, my sister, not being interested at the time, never followed this up. She also remembers him sitting and staring into space and she asked him what he was thinking about and his reply was “I was just in the trenches”.

Once, when I was doing my French homework, he told me he could speak French and I didn’t believe him so he said “Voulez-vous promenade avec moi ce soir?” which means “would you like to walk with me tonight”, so as his diary attests when he visited Amiens on the 26th August he “had a ripping time”; good times sometimes then.

His mother died in 1920 and he went to live in lodgings but in 1925 he married my mother and he bought a house in Oxford Street, Normanton. He also went back to work in the mines. The work was very arduous and he had difficulty breathing because he had lost a lung and at one time he worked permanent nights as the work was easier. He used to go to work on a bike and sometimes he would feel very ill cycling to work and suffered numerous bouts of pneumonia and bronchitis as he grew older. He went to work throughout the 1926 General Strike because he didn’t agree with it and he was a very principled man. He used to have a police escort to work and suffered a lot of verbal abuse but after the Strike some of the men who had called him names thanked him for helping keep the mine going. He was made a Deputy, got his Shotfirer’s Certificate and even studied Pitman’s Shorthand.

Another effect of the gas poisoning was his eyesight, he was almost blind in one eye and his other eye deteriorated over the years so he could hardly see at all. He had cataracts removed from his eyes and one time he had an operation on one of his eyes and he had to have one of his eyelids sewn together for six weeks. I think they were trying to rectify his sight but it didn’t work. He had to have a contact lens in his good eye which in the 1960’s were quite thick plastic which fitted over the whole of the eye. It had to be filled with liquid, stuck on a little suction pad and inserted into the eye. This he did every day. On top of the contact lens, he had glasses and still he had to use a magnifying glass to read the newspaper. From time to time he had to go to the then Department of Social Security, now the Department of Work and Pensions, at Lawnswood, Leeds, for assessment of his disabilities, I presume relating to his pension.

As he got nearer to retirement his health was becoming very poor and he couldn’t afford to retire early but he was told by a member of the British Legion that he may well qualify for a war pension but as my father had taken a lump sum on discharge he didn’t think he would qualify. However through the efforts of the British Legion a doctor came out to the house and he was eventually awarded a 75% war pension to which he said “I must be ¾ dead then”. This enabled him to retire early at 63 and to enjoy his retirement, which he did enormously.

He and my mother had four children, my brother, two sisters and myself, who came along when he was 54. He was a good husband and father and always instilled in us his good values and the necessity of having a good education and because of him we are who we are today.

He died on 4th November, 1969, and he had told my sister to ensure that my mother got the War Widow’s Pension, so a post mortem had to be done and my sister and my mother had to appear before a panel. It was found that one of his kidneys wasn’t working and the other was only working 50%, he had an enlarged heart due to having to work harder to help with the breathing. One of the members of the panel said “One wonders why he went back into the mine” and Philip Gill, who was the coroner at the time just said “economic necessity”.

My father’s death was attributed to congestive heart failure due to chronic bronchitis and emphysema resulting from the effects of poison gas whilst on War Service in 1914/18 war and this verdict enabled my mother to get her War Widow’s Pension.

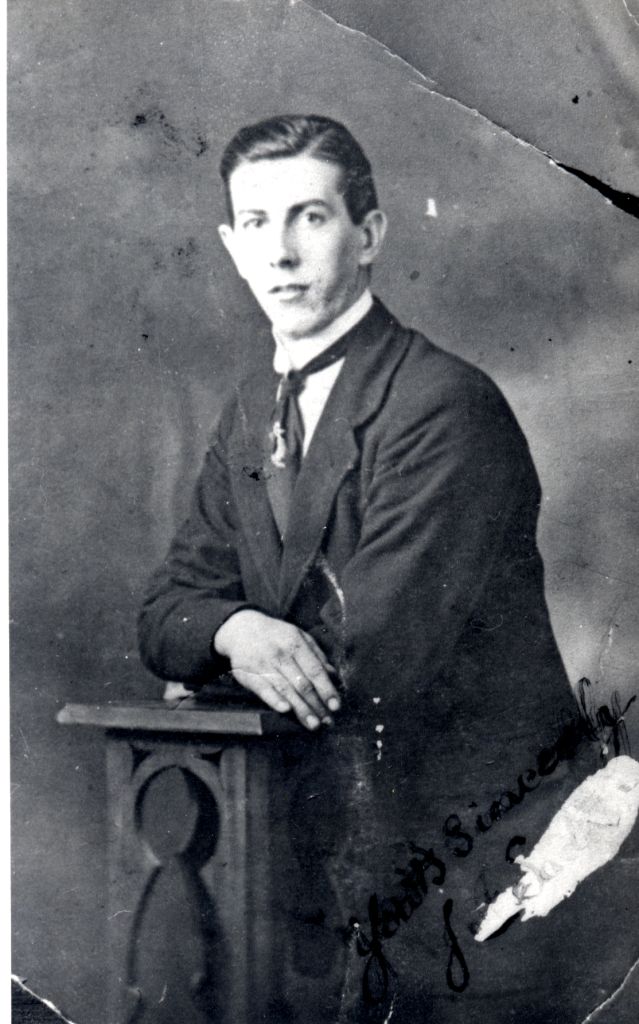

Joseph Arnold Sadler before the war

Joseph Arnold Sadler before the war

Joseph Arnold Sadler in his army uniform

Joseph Arnold Sadler in his army uniform

Joseph Arnold Sadler, far left, with a group of soldiers

Joseph Arnold Sadler, far left, with a group of soldiers

Joseph Arnold Sadler, sitting cross legged

Joseph Arnold Sadler, sitting cross legged

Joseph Arnold Sadler's diary

Joseph Arnold Sadler's diary